New York

CNN

—

Hours before President Donald Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs were set to take effect last month, he said, “These countries are calling us up, kissing my a**. They are dying to make a deal. ‘Please, please, sir, make a deal. I’ll do anything, I’ll do anything, sir.”

But the reality was that deals were not free-flowing. Instead, financial markets tanked after the tariffs took effect as impacted nations readied up retaliation plans, deepening the already steep losses markets experienced after Trump unveiled the rates on April 2. Even some of Trump’s biggest supporters begged him to back down.

Just over 12 hours after the tariffs took effect at 12:01 a.m. ET on April 9, Trump announced a 90-day pause, ostensibly to buy more time to work on “bespoke” trade deals with impacted countries, he said.

In the weeks since, Trump and administration officials have been constantly teeing up a slew of trade deals, claiming they’re imminent. Talk is starting to get cheap — or, perhaps, more expensive.

As Trump’s self-imposed July 9 deadline for when “reciprocal” tariffs would resume inches closer, just one deal with the United Kingdom has so far been announced. Trump and administration officials are starting to hint at cracks in their plan to get individualized trade deals done in time.

They blame it on other countries not negotiating in “good faith,” without elaborating on what that means. The punishment for that, though, is potentially even higher tariffs than the scorching rates announced in April.

“At a certain point over the next two or three weeks, I think Scott and Howard will be sending letters out essentially telling people — it will be very fair — but we’ll be telling people what they’ll be paying to do business in the United States,” Trump said last week, referring to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick.

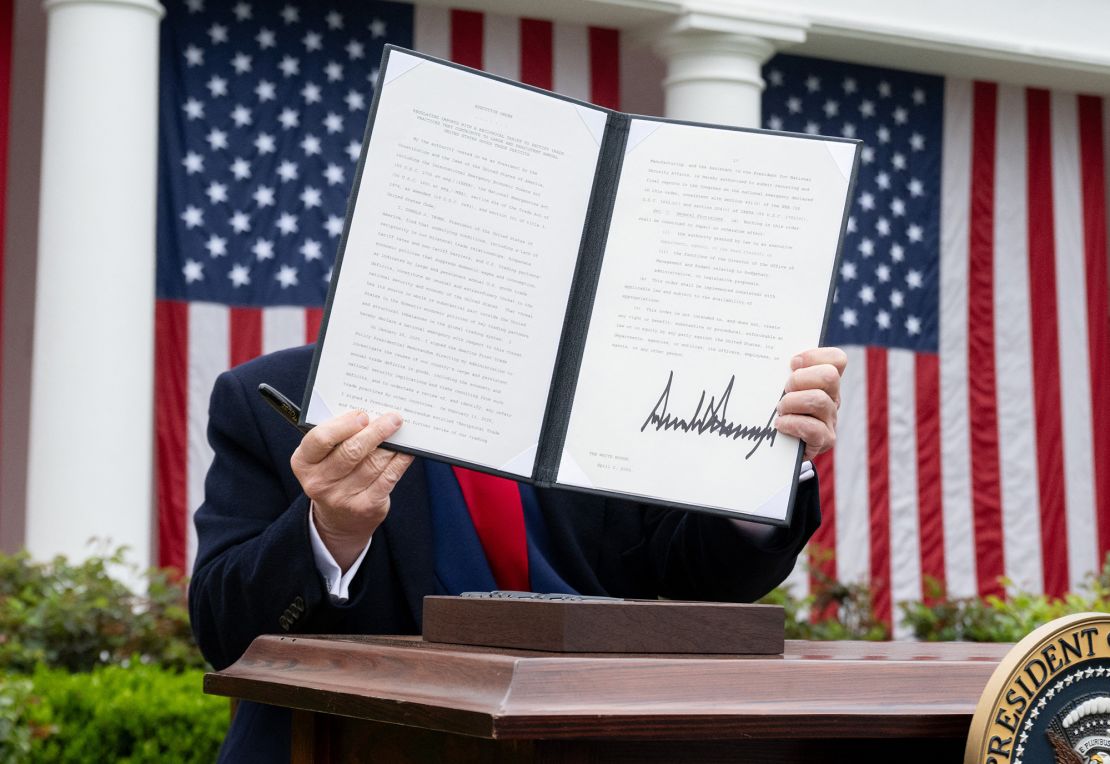

For reference, Trump also called his initial “reciprocal” rates, which went as high as 50%, fair. “The tariffs will be not a full reciprocal. I could have done that, yes, but it would have been tough for a lot of countries. We didn’t want to do that,” Trump said at his April 2 Rose Garden event where he initially unveiled the tariff rates.

In a Sunday interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper, Bessent alluded to a regional tariff scheme under consideration. “My other sense is that we will do a lot of regional deals: ‘This is the rate for Central America, this is the rate for this part of Africa,’” he said.

If that’s the case, countries with relatively lower rates that are near China, the administration’s prime target for higher tariffs, are likely to face elevated levies.

The White House and the US Treasury did not respond to CNN’s inquiry regarding whether a country’s proximity to China could influence the tariff rates it sees if a regional strategy is pursued.

“The Trump administration’s trade team is working around the clock to negotiate with other countries who do not want to lose access to the American economy, the biggest and best consumer market in the world,” Kush Desai, a White House spokesperson, told CNN in an emailed statement.

“President Trump has been clear, however, that new trade deals must be custom-tailored to reduce the unfair trade barriers that have left American industries and workers behind,” he added in a statement to CNN.

On the surface, the regional tariffs Bessent floated may sound somewhat arbitrary, since the administration has broadly said each trade deal would be bespoke.

So, shifting to a system where countries are grouped together under blanket tariff policies risks, in some cases, throwing out the baby with the bathwater for countries whose trade practices are less disturbing to the administration.

But there is an important practicality element to it, said Keith Rockwell, a former director at the World Trade Organization who is now a senior research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation.

As it stands, there’s a highly complex classification system the United States uses to assign tariff rates to specific products. The classification system is so granular that there are over 17,000 unique tariff product codes. If every country the US trades with has its own unique tariff rate in addition to the product rates, there would be millions of tariff combinations, he said.

That’s why the WTO has what’s known as “Most-Favored Nation” tariff rates for its 166 member countries, which essentially is a ceiling of mutually agreed-upon import taxes, though those can vary by sector. “There’s a reason why you negotiate things on a Most-Favored Nation basis: it’s just a heck of a lot easier,” Rockwell told CNN.

Furthermore, that is why countries are often drawn to entering regional trade agreements that can simplify and lower tariff rates. Some examples involving the US include, the United-States-Mexico-Canada Agreement and the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement.

But grouping countries together poses another risk: It gives them more ammunition to retaliate against the United States than if the individual countries were on their own, he said.